"In the long run, I think the founder-led companies outperform most other companies. Founders just care more. They have more of a long-term orientation."

- Mark Zuckerberg

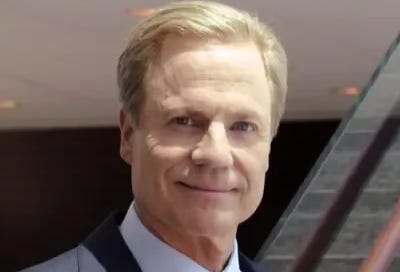

The longest-serving founder/CEO of a financial services company is Warren Buffett. Richard Fairbank, founder and CEO of Capital One, is second on the list. Buffett is a household name, of course. Fairbank much less so, and he clearly likes it that way.

The success of founder-led companies is not an urban legend. In a study of public companies run by their founders from 1990 to 2014, the consulting firm Bain showed that founder-led companies performed four times better than their counterparts.

No other top ten US financial institution is run by its founder - of course, this is mainly true because no matter how committed of a founder you are, it’s quite tough to stay alive for two hundred years.

Capital One is also run by a founder who keeps a low profile.

Here’s a test you can run yourself: do a search for Jamie Dimon (CEO of JPM) on YouTube. For Jamie Dimon, you will find thousands of videos - railing against Bitcoin at Davos, opining about inflation on CNBC, engaging with Elon Musk at the New York Times Deal Summit. It goes on and on.

Then do a search for Richard Fairbank, and you will find a total of six or seven videos. For me, the third search result is a recent high school graduate named Richard Fairbanks, who is interested in a career in magazine journalism (sounds like a great kid, though I’m not sure I’d recommend magazine journalism right now).

Fairbank doesn’t travel often and spends most of his time with his large family on a farm in Northern Virginia. He avoids conferences with other elites and tends to stay off the radar when it comes to speaking publicly. This separates him from both tech CEOs and flashy bank leaders in a profound way.

Yet, you’d be mistaken to confuse his avoidance of the limelight with a lack of boldness.

This is the story of Capital One’s rise in four acts: its disruptive entry into the market, its transition towards becoming a legitimate bank, its digital transformation, and its potential acquisition of Discover. Through this lens, we’ll examine how Fairbank's leadership and vision have shaped the company.

Act One: The Disruptive Upstart (1997- 2003)

Fairbank is the son of two successful physicists. His father worked on the Gravity Probe B, a satellite-based experiment that was launched to test two unverified predictions of general relativity. There’s a scientific rigor to Fairbank’s approach that bears mentioning, as he told a group of Stanford students in the late 90s:

“The (credit card) industry lends itself to massive scientific testing because it has millions of customers and a very flexible product where the terms and nature of the product can be individualized."

Fairbank started his career as a consultant. In the 80s, he worked at Strategic Planning Associates (now part of Oliver Wyman). During a project for a bank, he and Nigel Morris identified a huge opportunity in the credit card industry. They saw that credit cards were a large and quickly-growing segment for most banks, but that they were missing a giant opportunity to scale these products more quickly.

Before Capital One, credit cards were basically binary products. You either got approved or denied for a card. If you were denied, no credit for you, them's the breaks. But if you were approved, you were lumped into a uniform risk pool. The annual rate was about 18% for everyone, and the probability of default was treated identically. Fairbank and Morris realized that banks could leverage information about their customers to offer a range of credit card products at different rates.

The idea, as with most breakthrough business models, seems utterly obvious in retrospect.

It was certainly not obvious to the banks. Fairbank and Morris hit the road with their idea in 1990, pitching twenty card divisions and CEOs on their idea. No one bought it. Credit cards were already a profitable business for these institutions, and they balked at any idea that would cause charge-off rates to increase (one CEO even threatened to “throw Fairbank out of the window if he ever again recommended a business with charge-off rates over one percent”).

Finally, Signet Bank (now Wells Fargo) agreed to try the project, so Fairbank & Morris headed to Richmond to spearhead the idea. After a rocky start during which charge-offs immediately climbed from 2% to 6%, they hit on a winning idea in 1992: a teaser rate that enticed cardholders to transfer their credit card balances to Signet. This innovative strategy offered low introductory interest rates, making it highly attractive for customers looking to reduce their credit card debt. The results were staggering: Signet was hiring 400 people a month just to handle the volume of balance transfer applications.

By 1994, Signet became the best-performing stock on the NYSE, and the bank agreed to a spin-out of the credit card business. Fairbank would head a new entity called Capital One.

Fairbank continued to test prolifically, largely through direct mail offers; Capital One became the US Post Office's largest customer during much of the 1990s. It's tough to imagine an earlier example of A/B testing at this scale - in 1999 alone, Capital One conducted 36,000 tests. The key to the success of the testing was its integration up and down the stack - they weren’t just testing different types of marketing messages, they were testing everything - the products, the messaging, and all the nuances in between. Of the 36,000 tests in 1999, 80% were for products that did not yet exist. Without the A/B testing software that would automate this process a decade later, the entire system was managed by a spreadsheet so large that it maxed out Excel’s column limits.

By the end of the decade, Capital One’s unprecedented level of marketing and product customization began to dominate the credit card market.

Act Two: The Maturation: 2003 - 2012

Two events poured concrete into Capital One’s foundations during the 2000s: bank acquisitions and the 2008 banking crisis.

Bank Acquisitions

"We have a powerful credit card business, but the elephant in the room is we're a monoline. And we have to change that. This (Hibernia) deal enables us strategically to take the next big step."

As Capital One's credit card business thrived, the company recognized the need to diversify its operations and reduce its reliance on the volatile credit market. In 2005, Fairbank acquired Hibernia Corporation, a Louisiana-based bank, for $5.3 billion.

The headwinds facing the acquisition were strong, literally and figuratively. The market was skeptical of Capital One’s move to acquire Hibernia, and then Louisiana was pummeled by Hurricane Katrina, which leveled the bank’s home base. Fairbank stuck with the deal, and his resilience would pave the way for the acquisitions of North Fork in 2006, Netspend in 2007, and Chevy Chase in 2009. By 2010, Capital One would have over $120 billion in deposits, changing their risk algorithms for lending in fundamental ways.

Before the bank acquisitions, Capital One's funding strategy for its lending activities relied heavily on securitization and borrowing from capital markets. The company would pool large numbers of credit card loans and sell them as asset-backed securities to investors. This approach allowed Capital One to free up capital and continue originating new loans, while often retaining a portion of the securities on its own balance sheet. Additionally, the company would issue senior and subordinated debt notes to fund its lending operations, leveraging its strong credit ratings and market reputation to secure favorable borrowing terms.

This model had inherent risks. Securitization and capital markets borrowing are highly dependent on favorable market conditions. During periods of financial stress or uncertainty, these funding sources can become prohibitively expensive or even unavailable, leaving the company vulnerable to liquidity risks. Furthermore, unlike traditional banks with large deposit bases, Capital One lacked a stable, low-cost funding source for its lending activities.

Capital One's strategic acquisition of traditional banks was pivotal in stabilizing its lending sources and reducing its reliance on volatile capital markets. Initially dependent on securitization and market borrowing, Capital One faced significant risks during financial downturns. By acquiring these banks and accumulating a large pool of deposits by 2010, Capital One transformed its funding model. This shift provided a stable, low-cost funding source, fundamentally altering their risk profile and enabling more resilient and sustained growth in their lending operations.

The Great Recession

"We have always believed that you have to be willing to lend across the credit spectrum but that you must build the capability to manage the risk extremely well. That has allowed us to be successful over the years, including through this particular downturn."

Capital One had begun tightening its lending standards before 2008. Minimum credit score requirements were raised, and they tightened up their income verification process. Credit limits also went down, and consumers were allowed a lower debt-to-income ratio. Of course, charge-offs still went up in the wake of 2008, and overall spending reduced substantially. Despite that, the bank was prepared, and they were among the first group of major institutions to return TARP funds, doing so in June of 2009.

It wasn’t a surprise that Capital One did so, given their tightening credit standards and relative lack of exposure to mortgage-backed security products. Yet, there was something about a subprime lender making its way through the first large banking crisis in its relatively short history with relative ease. Capital One had arrived as a bank.

The bank didn't just survive the recession. Fairbank capitalized on the downturn, securing favorable terms in the acquisitions of Chevy Chase and ING Direct, an internet-only pioneer in digital banking.

ING Direct served its millions of depositors almost solely through the Internet and phone support. Its online capabilities were far ahead of most other banks at the time. The ING acquisition represented a shift in Fairbank’s perspective that kickstarted Capital One’s digital transformation.

Act 3: The Digital Transformation (2013 - 2024)

“I think it’s a bit of a fool’s errand…to chase digital for the sake of cost reduction.” -

Fairbank would now turn his attention towards modernizing Capital One from the ground up.

Beyond Fairbank’s boldness, Capital One had two major advantages that enabled it to transform its business for the age of cloud computing:

First, Capital One was built on data. Fairbank didn’t need to be convinced to adopt technologies that increased his ability to leverage data and personalization. His business achieved breakthrough success because of these things (of course, he managed to do so in Excel the first time around, which is a lot cheaper than AWS and Snowflake).

Secondly, the company was relatively young compared to banks that had been around for a hundred years or more. Companies don’t just accumulate technical debt; they also accumulate bureaucratic debt, and the latter may be even more pernicious when it comes to digital transformation. Fairbank had a company with a few decades of bureaucratic debt, but compared to its much older rivals, it was like a garage startup.

Fairbank capitalized on the above advantages and announced that the bank would be exiting its data centers and going all in on the public cloud during the bank’s Q1 2016 earnings call. In the 90s, Capital One had been the US Postal Service’s largest customer. It would now become the largest customer at AWS.

Digital transformation at a large company is a messy process. Most financial institutions had become dependent on third-party consultants, relying on them to maintain core banking systems and ERP software for decades. These consultants still operated on the “IT Outsourcing” model, which was born during the Y2K scare. This model was built on staffing hundreds of bodies, often halfway around the world, at the cheapest price possible. When the model adapted towards the implementation and maintenance of ERP systems in the 2000s, the general principle remained the same - cheap bodies with minimally viable skills.

Without exception, this led to large institutions accumulating two decades of technical debt, and the result was complexity and labor bloat. So Fairbank’s first move would be to transform his labor force, prioritizing full-time employees whose skill level could be controlled with internal standards. He also acquired a few digital agencies, including design firm Adaptive Path and cloud-based app development firm Monsoon (my previous consultancy).

Capital One became the first large bank to migrate to the public cloud, and they invested heavily in digital capabilities across the board including mobile banking, machine learning, and sophisticated DevOps. The difference between them and other banks, however, was that these capabilities were being built in-house. They were among the first banks to launch a mobile app, allowing customers to manage their accounts, pay bills, and transfer money from their smartphones. They also developed sophisticated fraud detection systems using AI algorithms to protect their customers' data and transactions.

In my twenty years working on digital transformation for large companies, I have never seen this process go smoothly - and Capital One was no exception. The stock often took a beating during this period, as investors couldn’t grok the long and bumpy 11-year journey towards modernizing infrastructure. To make matters worse, a Seattle engineer hacked into Capital One’s cloud environment in 2019 and made off with 100 million credit applications. Fairbank and his team stayed resolute through all of it, continuing to invest billions in technology despite the beating he took in the market.

And today, Capital One has the best technical infrastructure of any US financial institution of a similar size. It is the world’s largest FinTech.

Phase 4: The Network?

“We have always had a belief that the Holy Grail is to be able to be an issuer with one’s own network.”

Capital One’s potential acquisition of Discover would be a seismic event in the history of the US credit card industry.

The credit card industry is relatively young when compared to banking. The credit card network was born in 1970 when Dee Hock, a middle manager at the Seattle National Bank of Commerce, convinced Bank of America to take its nascent BankAmericard program and transform it into a non-profit network that would become the rails for the modern credit card network and one of the largest corporations in the world: Visa.

“Any organization that could guarantee, transport, and settle transactions in the form of arranged electronic particles twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, around the globe, would have a market—every exchange of value in the world—that beggared the imagination,”

- Dee Hock

Today, Visa has over 80 million merchants and 4.3 billion cards in circulation. They make a 70% margin on the processing fees for transactions, which totaled $12.6 trillion dollars of payment volume over the last 12 months alone.

Dee Hock, the “father of FinTech”, leveraged network effects to revolutionize payments and pave the way for the digital revolution. Today, Visa and MasterCard have developed a private protocol for payments that has enabled them to sit amongst the most valuable financial institutions in the world.

They are also powerful brands. Customers know when they are paying with Visa or Mastercard: in fact, at the moment of purchase, they are more conscious of their card network than they are of the bank that issued the credit card to them in the first place. The opposite is true in most other use cases. No one ever thinks “I’m sending this email to you with SMTP”, because that part is generally invisible. They just know they are using Gmail. Yet, we are conscious of the card network almost every time we make a virtual or physical purchase. Store windows around the world have Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover logos on their windows. They use this valuable real estate to let customers know that they will be able to make purchases with their preferred card.

For Capital One, the potential acquisition of Discover vertically integrates their business and gives them a new level of brand recognition, one that extends around the world. Of the largest US banks, Capital One is one of the few that has an incidental international presence. Discover turns them into an international brand overnight.

Most importantly, they gain ownership of a powerful credit card network, enabling them to compete directly with Visa and Mastercard. The vertical integration would allow Capital One to control the entire credit card value chain, from issuing cards to processing transactions and managing merchant relationships.

Like Capital One, Discover was a latecomer to its niche. It didn’t get to the market until 1985, thirty-four years after the launch of Visa. Discover was launched by the Sears Corporation, who at the time, had a customer base large enough to enable it to issue 33 million cards by 1989.

Today, while Discover accounts for a small fraction of total credit card transactions, it is accepted widely. Customers can use Discover cards in locations that account for 90% of total card transactions.

Capital One’s acquisition of Discover would result in a combination that holds over $250 billion dollars in credit card loans, which would surpass the $211 billion held by the current largest lender, JP Morgan. The potential to scale this business even further is clearly attractive to Fairbank.

“The credit card business – and I think this really applies to consumer financial services businesses in general, but certainly to credit cards – are very scale-driven, and I think, in many ways, more scale-driven than a lot of other parts of banking.”

Capital One believes the merger would also lead to over a billion dollars in savings on operational and marketing expenses.

The acquisition faces stiff opposition from politicians such as Ro Khanna and Elizabeth Warren.

They argue that the scale of the merger will reduce competition. In the opinion of this author, the argument is deeply flawed. Capital One is the 9th largest bank in the United States, and the acquisition of Discover would do little to bring their size any closer to the top four institutions. More importantly, this deal could increase competition at the level of the credit card network, which is one of the most highly-concentrated areas in financial services today. 90% of all credit card transactions take place over Mastercard’s and Visa’s credit card networks.

“And so we’re talking about taking a network that is way, way smaller than those and giving it a chance to get more threshold scale, pick up momentum… Over time, we’re going to lean in and build the strength, the acceptance, the brand and the perceived acceptance and the credibility of this network and then keep moving volume over as we get more traction along the lines.”

Fairbank intends to start with debit, with a plan to shift $175 billion in debit purchases onto Discover’s network by 2027. Credit will come later and will require Capital One to grow customer perception of how widely Discover is currently accepted throughout the market.

Once they overcome this hurdle, there are tremendous advantages to operating a closed loop network in which Capital One is both the issuer and the network. Capital One can take advantage of new network-enabled revenue streams and provide more value-added services to merchants and customers.

Most importantly, it gives Fairbank the opportunity to continue doing what he has done since Capital One’s earliest days: leverage increasing amounts of data to build breakthrough products.

Nice summary. One thing you missed was the that towards the end of the first act, Capital One was hit with a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) from the Federal Reserve, forcing the company to bring its business and credit practices up to the standards of the banking industry. Until that time Capital One was running like a startup, with limited controls that let the company move quickly but make mistakes. Once they became a large player, the Fed said that was no longer going to work. The MOU was a shot across the bow. At the beginning of the second act, much of the company's focus was on building controls that were required by the MOU. This was a painful process, but ultimately created a solid foundation for further growth.